At last a genetic study using fresh DNA evidence brings answers to centuries of questions about the decimation of indigenous island populations.

As the earliest inhabitants of the islands, the first Caribbean peoples claim an important part in regional history. It was long-believed that the demise of the indigenous islanders were wiped out by the arrival of the Spanish. However fresh DNA evidence and new genetic data suggests that South American invaders decimated the population of the Caribbean’s first people long before colonists came, wreaking havoc on islands across a million square miles.

Dotted with more than 700 islands, the Caribbean Sea was one of the last places colonised by Native Americans as they explored and settled North and South America. These intrepid seafarers have fascinated archaeologists who have long struggled to pinpoint their exact origins and movements. Now, thanks to genetic material gathered from the bones of ancient Caribbean residents, the invisible history of many of the Caribbean’s original inhabitants has come to light. It has been surprising and enlightening, rewriting Caribbean history: as it suggests that early Caribbeans were wiped out by South American newcomers a thousand years before the Spanish invasion that began in 1492.

Until just a few years ago, DNA technology couldn’t extract DNA from bones in warm, wet places like the Caribbean - but that has now all changed. Thanks to recent advances in genetic technology, a Harvard University lab was able to recover DNA from 174 individuals excavated at sites from Venezuela to the Bahamas - a scientific breakthrough.

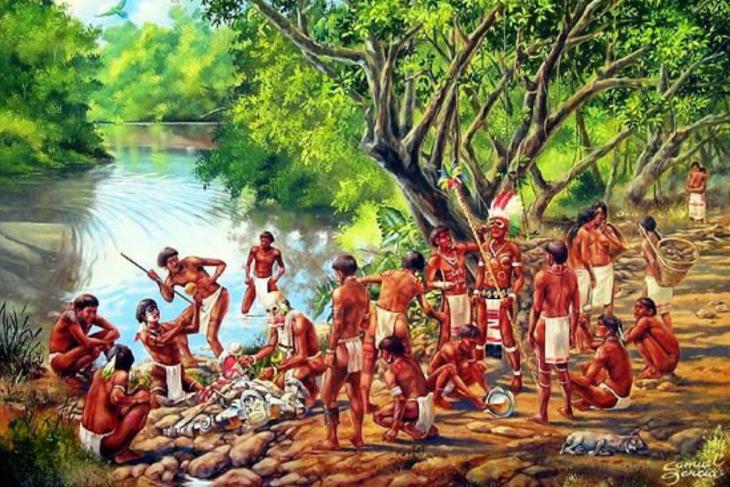

Further studies analysed the genomes of 93 ancient Caribbean individuals at a University of Copenhagen lab, to establish a detailed picture of the early migration history of the Caribbean. Research confirmed that a wave of pottery-making farmers from the northeastern coast of South America —known as Ceramic Age people—set out in canoes some 2,500 years ago and island-hopped across the Caribbean. They were not, however, the first colonizers. On many islands they encountered a foraging people who arrived some 6,000 or 7,000 years ago from the coasts of Central America and northern South America.

According to National Geographic magazine, these pottery-making farmers settled in such numbers that they largely replaced the islands' earlier inhabitants, who lived by foraging. The pottery makers continued to make and use stone tools similar to those used by earlier Archaic Age foragers, who seem to have largely vanished soon after the newcomers appeared.

On the faintest, limited genetic traces of Archaic individuals in the Ceramic Age people provides a clear indication that the two groups rarely mixed. The ceramicists, who are related to today’s Arawak-speaking peoples, supplanted the earlier foraging inhabitants—presumably through disease or violence—as they settled new islands.

Other intriguing findings from the Harvard study include DNA from a Lucayan woman who lived in the Bahamas in the 1300s. The genetic studies showed that the DNA of this indigenous group survives in modern-day islanders, mixed with genes from later European colonisers and enslaved Africans. However, one mystery yet to be resolved is how relatively small Caribbean island populations avoided inbreeding over so many centuries. There is no sign of any subsequent major migrations from the mainland. But archaeologists say the new evidence points to extensive island-to-island contacts that likely helped ensure genetic diversity.

Many indigenous groups have alleged that geneticists—often white Europeans and Americans—don’t consult with them, or show proper respect for their traditions, while investigating their origins. In this case, however, the authors of the report said they collaborated with descendant communities as well as local Caribbean scholars in gathering and analysing their data. The research was supported in part by a grant from the

National Geographic Society.